I don’t have to wait long to be seen—maybe because I’m so sick or maybe because the doctor from the walk-in clinic alerted the ER, as she said she would—but I am in the waiting room long enough to be reminded what a microcosm of the human condition the hospital is: All walks of life brought together by all sorts of maladies. People whose paths you quite likely would not cross save for the fact that you are all in need of medical attention.

One woman complains that others, who came in after she did, are being seen before her. Another alerts us to the children who are playing with plastic spoons near an electrical outlet.

“If those were metal those kids would get shocked. Electrocuted, maybe.”

An older man eats a hamburger, a teen texts, and I think I recognize a lady from my church. There is just enough time for me to begin (okay, so I’ve been doing it since I woke up) ruminating on chance, luck, Divine purpose, the vagaries of life, before I’m called back by a nurse.

I’m put in a room, and the blood draws and IVs are underway almost immediately. My nurse, the first of several, is lovely. She talks me through everything she’s doing. I feel so bad I don’t really care what they do to me, but I appreciate her treating me with respect.

This is what I am thinking: This is how people find out they’re really sick. Someone’s husband is parking the Subaru with the dog slobber on the backseat windows and a doctor comes in and says something life-changing. On an otherwise normal day, people get bad news all the time. This is how it happens, without fanfare or warning or your loved one having time to get back from the garage. You have a fever and no energy and your life unravels. The old “Why me? Why not me?” toss up.

I begin to weep.

It’s an actual room, not just a curtained corner, so I do have privacy, which is nice. When it’s determined that I’ll need to be admitted, and there’s not a room available, the nurse has a hospital bed brought in, so I can get off the thin mattress that reminds me of the fold-out mat I used in kindergarten at naptime. It is a thoughtful thing to do and I am grateful. Any comfort–like the nothing short of a miracle shampoo shower cap–in this storm feels like a life preserver.

There is a lot going on out there.

Someone (as I make my way to the bathroom later I see a policeman in the hall) yells for a man to get back in his room. Apparently he doesn’t realize that being under arrest means you can’t just go tooling around the ER willy-nilly.

Several medical professionals come and go from my room. I am asked the same questions by different individuals. I think my answers are pretty consistent: Been feeling a bit poorly for a week or so but not alarmed until this morning; no I haven’t been out of the country; no I didn’t notice a tick or a rash on my body; yes I get yearly physicals; no I haven’t seen blood in my urine; no I don’t smoke.

One man, let’s call him Doctor X (not his real name) shall we, pulls a chair close to the bed and gets even closer to my face.

“Ms. Wilson.” Pause. “What do you think is wrong with you?”

His tone makes me feel like a kid, when my mother would ask me, “What do you think you did wrong, sweetheart?” (For the record, she did not have to ask me this often as I was an exemplary child. Or so the story goes.)

“I have no idea,” I say, when what I am thinking is more along the lines of, “If I knew, I promise I’d tell you. If I had a nagging suspicion, a mere inkling, any semblance of intuition, a scrap of insight, I’d share it with you.”

He makes me feel as if I am holding something back, as if I don’t want them to know everything they need to know in order to figure out what is happening with my body.

“What about HIV? A lot of times these low white cell counts indicate HIV.”

“I don’t think so,” I said.

“You’re not at high risk, you don’t think?”

“No sir.”

“Multiple sex partners? Drug use?”

“No sir.”

I don’t have the strength for regaling him with all the reasons I don’t think I’m a candidate for HIV, and I feel so bad I start to think maybe I’ll be some fluke case of contracting it. It could happen, I guess. I don’t have an issue with the testing; test away. I have an issue with the delivery. Why not something like, “It’s standard for us to test for HIV when we see such low white counts.” More equalization; less shame.

“Okay, well. You need to know that this could be serious.”

Again, maybe you could try: “We don’t know what’s wrong with you but we’ll do everything we can to find out. It could be an infection, or it could be something more serious.”

So, um, Doc, I’m already convincing myself I might be dying. I’m in the ER, so I get it, that this might be serious. To me it already is. I’m way ahead of you.

Doctor X leaves and comes back so fast I’m surprised he had time to turn around.

“I’m testing you for HIV.”

“Okay,” I say. “Fine. Of course.”

Long an admirer of

Long an admirer of  Upon returning to Nashville my husband and I went to hear

Upon returning to Nashville my husband and I went to hear  I applied for a job at The Sun a while back and although I made the first cut, being invited to critique issues of the magazine, I was not called for an interview. I’m glad I didn’t let any disappointment keep me from attending this retreat. For there is always something to learn about the practice of writing, a bit of inspiration to glean, a recommendation to take to heart, a fellow pilgrim to meet.

I applied for a job at The Sun a while back and although I made the first cut, being invited to critique issues of the magazine, I was not called for an interview. I’m glad I didn’t let any disappointment keep me from attending this retreat. For there is always something to learn about the practice of writing, a bit of inspiration to glean, a recommendation to take to heart, a fellow pilgrim to meet.

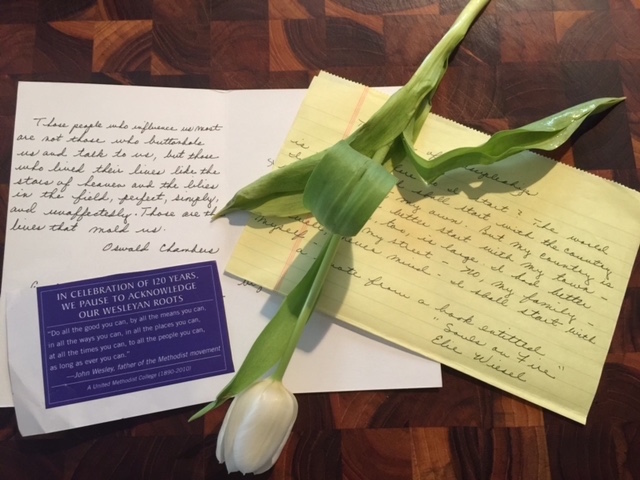

Instead of regaling people with charming anecdotes about my childhood (dancing to “I’m a Little Teapot” in the living room) or relaying repetitive accolades (“Your mother was one of the most influential people in my life.”) about how precious my mother was—and she was dear—when giving her eulogy on February 23, I instead read three passages I dug out of one of my “memory boxes” while crying and packing my suitcase for Mississippi after my sister Ann phoned to say, “This is the call you never want to get.” Bits and pieces from a long life well lived that illustrate, better than a hundred family snapshots, what made Martha Lee Lyles Wilson (1922-2016) such a remarkable woman.

Instead of regaling people with charming anecdotes about my childhood (dancing to “I’m a Little Teapot” in the living room) or relaying repetitive accolades (“Your mother was one of the most influential people in my life.”) about how precious my mother was—and she was dear—when giving her eulogy on February 23, I instead read three passages I dug out of one of my “memory boxes” while crying and packing my suitcase for Mississippi after my sister Ann phoned to say, “This is the call you never want to get.” Bits and pieces from a long life well lived that illustrate, better than a hundred family snapshots, what made Martha Lee Lyles Wilson (1922-2016) such a remarkable woman.